In part one of a double feature this Black History Month, we are taking a look back at Oldham’s past, and its complicated relationship with slave labour in the United States.

You don’t have to look far to find a mill in Oldham. While there are fewer than there used to be, what is now the borough of Oldham has seen more than 400 mills, built as far back as the late 1700s, to manufacture textiles.

The industry, and those who worked in it, as well as those who were enslaved by people profiting from it, were responsible for turning Oldham from a small town into an industrial powerhouse.

According to the Revealing Histories project, the town’s population soared as the number of mills grew, from 10,000 people and 12 mills in 1794 to 42,595 people and 94 mills in 1841.

However, a cotton mill cannot run without cotton, and cotton meant big business, and enslaved Black Americans were often used as free labour, in appalling conditions – with people, including children, sold as property, and treated in many cases worse than animals, subject to vicious beatings, rape, and murder.

Sign up to our newsletters to get the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

The abolishment of slavery led, in part, to the American Civil War – a conflict between the Union, mostly made up of northern states, and the Confederacy, mostly those in the South.

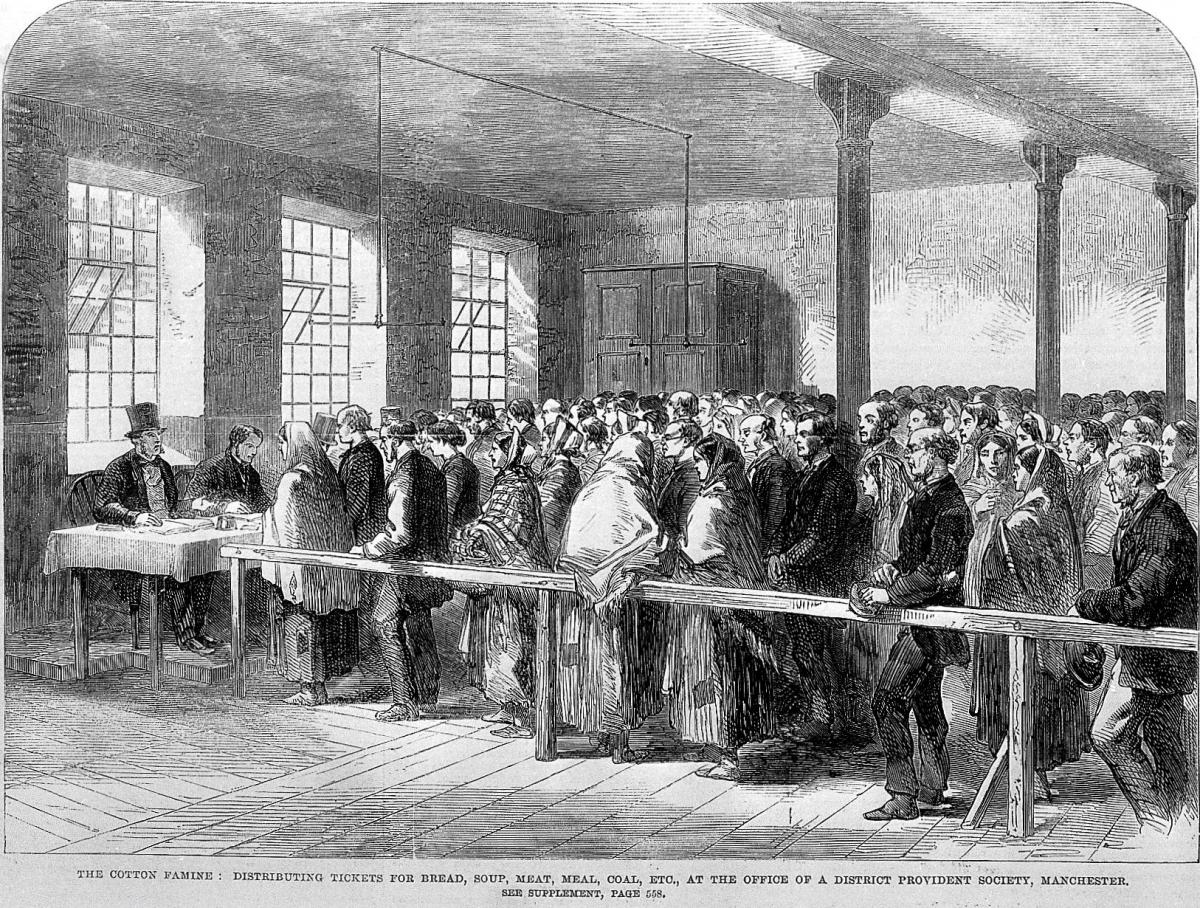

As part of the conflict, a blockade on cotton exports took place, leading to ‘devastation’ in Oldham in the form of a ‘Cotton Famine’, which lasted from 1861 to 1865.

Dr Natalie Zacek is a senior lecturer in English and American Studies at the University of Manchester.

Speaking to The Oldham Times, she said: “Because the Union navy had blockaded the southern ports, it was almost impossible to get cotton out of the plantations of the American south to the North West, and therefore textile workers were laid off in huge numbers because their employers could not get any cotton for them to work.

“Oldham, even compared to some of the other towns around the North West, was very badly affected.

"A lot of the people in Oldham who had supported themselves as cotton workers were in a particularly bad situation.”

Support and opposition to slavery

While slavery was supported by the elites of Liverpool – Britain’s main slaving port during the 18th century, those in Lancashire were more likely to be against the practice.

After cotton workers in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall sent a letter of support to US President Abraham Lincoln, he responded with thanks to the ‘working men of Manchester’ in 1863.

A statue now stands in Manchester’s Lincoln Square to commemorate the events.

Dr Zacek continued: “There was a lot of anti-slavery sentiment among the workers and the middle classes, particularly the more educated middle classes throughout the North West, which is why so many black and white abolitionists, first those hoping for the abolition of slavery in British colonies, and then after slavery ended in the British Empire in 1834, focussing on abolishing slavery in the United States.

“This was a particularly fertile territory for abolitionists to tour, to raise awareness and money.

"Lancashire was really the most anti-slavery part of Britain, and probably of Europe, at the time.”

Follow The Oldham Times on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Threads.

Contemporary reminders of the past

Reminders of Oldham’s historical links to slavery are dotted around the borough. You do not have to look far to find a chimney towering above the skyline, to remind you of mills which once handled cotton produced by slave labour.

However, Alexandra Park is another part of the borough with links. The park was built in the 1860s as a labour project for those left unemployed during the cotton famine, as now commemorated by a blue plaque.

Dr Zacek said: “So many people, adult men, adult women and older children were employed in the textile mills in various capacities. The mills had to shut down because they were simply not receiving any cotton at all.

“This is an era before there’s any kind of public welfare, so if you lost your job – even though in this case it was not in any way the worker’s fault – and you couldn’t easily find another one, you had to hope that you had friends or relatives that might help you, or there was private charity, especially through religious groups.

“Those groups were overwhelmed by applications for relief, and there also were some attempts by local governments or local wealthy people who were not connected to the textile trade to make work projects.

“So, I know that Alexandra Park was pretty much made by unemployed textile workers who were paid. A park was seen as a nice thing to have, but it wasn’t really necessary, so it was financed locally to help employ some of the men who had been thrown out of work.

“There were even projects that weren’t real projects, like dig a hole in the morning, fill it in in the afternoon. There was a real reluctance to pay able-bodied men to not work.

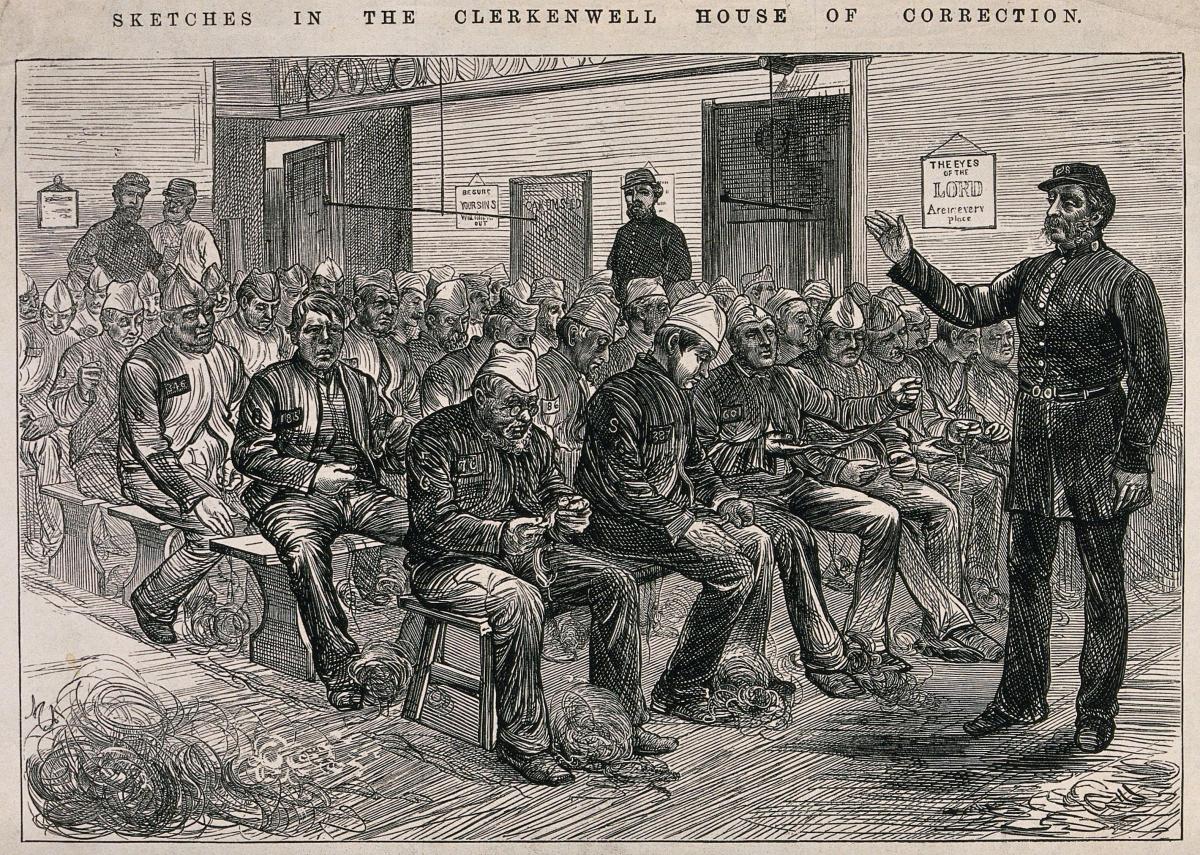

“You could go to the workhouse, it was better than starving, but it was made to be just better than being homeless and starving.

“Husbands were separated from wives, parents from children, and the work was usually picking oakum which was a wretched kind of work, you were given a bed and you ate.”

Next week

Next week we will be looking further at Oldham’s relationship with slavery, taking a closer look at the attitudes of Oldhamers at the time towards it.

We will also be looking at the story of one enslaved Black American, James Johnson, who found his way from North Carolina to Oldham, where he settled and wrote his life story into a pamphlet, which we will be publishing online in full.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here